Kuo Pao Kun wrote The Coffin is Too Big for the Hole in 1984, eight years before his citizenship was reinstated. Yet this play is one of the most widely known of his productions, and has been performed both locally and internationally, and is considered a seminal piece of Singapore literature. In this case, what makes this work of Singapore literature uniquely Singapore?

More recently, the film by Tan Pin Pin To Singapore, With Love, also features ex-Singaporeans who were exiled due to the "political unrest" they brought to the nation. Yet, despite the events being in the distant past, despite their physical banishment from Singapore, their feelings for the nation are still clearly visible.

Goh Poh Seng himself studied in Kuala Lumpur and Dublin, and throughout his book the use of Singlish is contrived and distinctly unnatural: clearly the local vernacular is not second nature to him, not something that he has grown up around. Rather, it is a way of distinguishing his texts as being Singaporean, a way to try and relate to his own fellow citizens.

Singapore literature is something that is not just tied to the physical locations that we are in, nor does it depend on a person's official citizenship status, or the ability to speak like locals speak. The idea of a literary work being able to represent Singapore as a whole is a dangerous misconception: each piece has a subjective view, and represents Singapore as the writer sees Her. To me, this does not make the articles any less meaningful. Rather, knowing the limitations of these literary works, I feel that the impression I get of Singapore becomes less rigid: each person takes away a different feel from Singapore, the relationship between the nation and the authors emerge in various literary forms, and ultimately the result is a menagerie which builds a more comprehensive view of Singapore as a whole.

Singapore - More than words

Monday, 3 November 2014

Sunday, 2 November 2014

Emerald Hill: an Erosion of Culture

Emerald Hill (also known as The Grand Old Lady with the Peranakan Airs), was designated for preservation under Singapore's Area Preservation Scheme in 1981. The 9.5 ha area received a complete facelift as part of the preservation scheme. In addition to the two-storey houses, the landscaped pedestrian walkways and surrounding areas were also preserved. The preservation works and recreation of the Straits Chinese environment was based on original 1902 architect plans.

|

| Emerald Hill in the past - before restoration |

|

| traditional wood-carved Peranakan doors |

|

| today |

|

| in the past |

Chew Yi Wei (in Eastlit Issue 5) beautifully describes her sentiments on Emerald Hill:

"Conservation efforts merely stimulate the past, giving us only a pretty, charming but ersatz image of it. Conservation is nostalgia with a lost cause. Can we not retain the past by leaving it alone? In a bid to keep the past, we sap the life out of it."

Such thoughts of a "smeared" culture echoes in a poem from someone who had visited Emerald Hill:

Emerald Hill

by Youzi

Tucked away watching

somewhere beyond the city scape

Silent, inconspicous

Cunningly masked,

By the intoxicating tastes and noises

of Sherry, Brandy, Port and Havana Cigars.

Swilling around her

Neither young nor old

And yet both

Somewhere she is smeared

Blue and white

In a grotesque parody of prettiness

Somewhere she retains

an ageless beauty

Golden carvings and warm rich wood

Still smelling of nutmeg, pepper and gambier

But most days now she doesn't care

Complacent vines

Weary leaves trail and her heels

She drapes herself

In dusty batiks patterned by dust

Caked with the smug patina of time

Not a sound

Save for the occasional gurgle

Of laughter from the see-saws

Where we grapples with loss like her

Not a soul

Save for the curious face behind the darkened windows

And the pink blouse flying alongside the reluctant wind

In the distance the fowls wander

Or look at us knowingly

They must have seen many like us

Who sat in her presence

Our hearts greedy for her knowledge

Who caressed her and praised her

Then left her cold

________________

References

(Photographs): rememberingsingapore.blogspot.sg

"Going Back to Emerald Hill" by Chew Yi Wei. Published April 2013:

http://www.eastlit.com/eastlit-issue-five/eastlit-april-2013-content/going-back-to-emerald-hill/

"Emerald Hill" by Youzi. Published Mar 2005:

The Importance of Appearance in Singapore

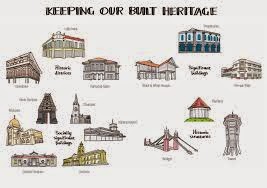

The Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) of Singapore prides itself on its conservation efforts. These efforts are intended to enhance the visual appeal of Singapore, as well as preserve the nation's rich heritage and tradition, reminding citizens of the past while the nation advances into the future.

The plans for conservation are elaborate. Firstly, different conservation districts are drawn up - historic districts (i.e Boat Quay, Chinatown, Kampong Glam and Little India), residential districts (i.e Emerald Hill, Cairnhill and Blair Plan), Secondary Settlements (i.e. Jalan Besar, River Valley, Geylang and Joo Chiat), as well as The Good Class Bunglow Areas and the Mounbatten Road Area. Guidelines on restoration work follow the 3R principle: Maximum Retention, Sensitive Restoration and Careful Repair. In short, a great deal of emphasis is on maintaining or adhering to a "certain look" or restoring the facade of tradition and culture in our otherwise extremely modern nation.

The photos below are evident of such attempts at conserving the structure and design of old shophouse buildings.

The need of up upkeeping appearances is mirrored not just in our city's architecture but also in the daily lives of Singaporeans. Such a way of life is evident in texts such as Kuo Pao Kun's The Coffin Is Too Big For The Hole and Stella Kon's Emily Of Emerald Hill.

In Kuo's play, the big, grand looking coffin was meant to signify his grandfather's wealth and position in society. Even at death, the family had to ensure that onlookers were aware that the deceased was a prominent person from a well-to-do family, hence the elaborateness and grandeur of the burial and coffin. Furthermore, throughout the funeral, the protagonist was very mindful of the onlookers, repeatedly emphasising that their family was "watched" by "two hundred people". Hence much of how he behaved and reacted to the whole fiasco of the coffin being too large for the hole was an attempt to "save face" for the family. This was to be done by ensuring that the funeral procedure is followed through according to tradition, and not become a joke - although this has been done to comic effect: "it must have been the funniest thing that ever happened in the entire history of mankind"(Poon et al, 2009: 291).

In Emily of Emerald Hill, we see Emily putting up a strong front and trying to present the family as if things were going smoothly although they were not. In spite of the turbulent and unfortunate events within her family, such as her first son, Richard's suicide, the fact that she is always alone in her huge Emerald Hill mansion (all her children have moved out) and that her husband no longer loves her and is having an affair, she continues to host an elaborate dinner as if all is well. We can see she succeeds as the Singapore Free Press even reports the social event as a "splendidly-attended dinner". Of course, one could argue that her purpose of doing so would be to "force" her husband to end his extramarital affair. In addition, Emily's throws a party to reinforce their marriage in order to try to end her husband's affair, while saving the reputation of her unfaithful husband. This is another instance where appearance is key to maintaining people's perceptions of something.

Clearly, Singaporeans are highly mindful of how they are perceived in each other's eyes and the image in which they or their families portray. This can be metaphorically transposed to the maintenance of the appearance of buildings or heritage sites achieved through conservation efforts, which perhaps struggle to keep the impression of culture and tradition alive.

All in all, the conservation efforts of the URA are commendable, but ultimately, authorities have to realise that mere preservation of facade without content is not true conservation as our culture and heritage still face erosion.

URA conservation website

http://www.ura.gov.sg/uol/conservation.aspx#

The plans for conservation are elaborate. Firstly, different conservation districts are drawn up - historic districts (i.e Boat Quay, Chinatown, Kampong Glam and Little India), residential districts (i.e Emerald Hill, Cairnhill and Blair Plan), Secondary Settlements (i.e. Jalan Besar, River Valley, Geylang and Joo Chiat), as well as The Good Class Bunglow Areas and the Mounbatten Road Area. Guidelines on restoration work follow the 3R principle: Maximum Retention, Sensitive Restoration and Careful Repair. In short, a great deal of emphasis is on maintaining or adhering to a "certain look" or restoring the facade of tradition and culture in our otherwise extremely modern nation.

The photos below are evident of such attempts at conserving the structure and design of old shophouse buildings.

pre-restoration

after restoration

_____________________

pre-restoration

after restoration

_____________________

today vs. in the past

_____________________

The need of up upkeeping appearances is mirrored not just in our city's architecture but also in the daily lives of Singaporeans. Such a way of life is evident in texts such as Kuo Pao Kun's The Coffin Is Too Big For The Hole and Stella Kon's Emily Of Emerald Hill.

In Kuo's play, the big, grand looking coffin was meant to signify his grandfather's wealth and position in society. Even at death, the family had to ensure that onlookers were aware that the deceased was a prominent person from a well-to-do family, hence the elaborateness and grandeur of the burial and coffin. Furthermore, throughout the funeral, the protagonist was very mindful of the onlookers, repeatedly emphasising that their family was "watched" by "two hundred people". Hence much of how he behaved and reacted to the whole fiasco of the coffin being too large for the hole was an attempt to "save face" for the family. This was to be done by ensuring that the funeral procedure is followed through according to tradition, and not become a joke - although this has been done to comic effect: "it must have been the funniest thing that ever happened in the entire history of mankind"(Poon et al, 2009: 291).

In Emily of Emerald Hill, we see Emily putting up a strong front and trying to present the family as if things were going smoothly although they were not. In spite of the turbulent and unfortunate events within her family, such as her first son, Richard's suicide, the fact that she is always alone in her huge Emerald Hill mansion (all her children have moved out) and that her husband no longer loves her and is having an affair, she continues to host an elaborate dinner as if all is well. We can see she succeeds as the Singapore Free Press even reports the social event as a "splendidly-attended dinner". Of course, one could argue that her purpose of doing so would be to "force" her husband to end his extramarital affair. In addition, Emily's throws a party to reinforce their marriage in order to try to end her husband's affair, while saving the reputation of her unfaithful husband. This is another instance where appearance is key to maintaining people's perceptions of something.

Clearly, Singaporeans are highly mindful of how they are perceived in each other's eyes and the image in which they or their families portray. This can be metaphorically transposed to the maintenance of the appearance of buildings or heritage sites achieved through conservation efforts, which perhaps struggle to keep the impression of culture and tradition alive.

All in all, the conservation efforts of the URA are commendable, but ultimately, authorities have to realise that mere preservation of facade without content is not true conservation as our culture and heritage still face erosion.

References

URA conservation website

http://www.ura.gov.sg/uol/conservation.aspx#

Poon, A.;

Holden, P.; Lim, S. (2009) Writing Singapore: An Historical Anthology of

Singapore Literature. Singapore: NUS Press.

Saturday, 1 November 2014

Conformity in Singapore

It is apparent that the government imposes many rules and policies in Singapore. On one hand, these laws can be seen as implementations to protect society, and people's rights and interests. On the other hand, these laws could be a way for the government to exercise its authority and perhaps even "over-nanny" the country.

During the National Day Rally in 2004, Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong touched on the issue of conformity:

"We are so capable, we are so efficient, we are so comfortable that we stick with what we have tried and tested and found working and we are reluctant to take risks and try new things. And that is a weakness. It's a weakness which we have to overcome. The key to overcoming this is a mindset change. We have to see opportunities rather than challenges in new situations, we have to be less conventional, we must be prepared to venture and you've got to do this as individuals, we've got to do this as a government and I think we have to do it as a society. "

This theme of "conformity versus eccentricity/opposition" is echoed in Edwin Thumboo's poem entitled Conformity, which compares the situation of individuals who thrived in "happy colonial days" by conforming to those who chose to rebel against the "colonial system" (Ee. T, 1997).

__________

Conformity

The very old died young

Having eased themselves out of

Ambition, calculating smiles,

Connived quietness.

They died softly in the dispensation

Of happy colonial days.

Properly cautious, they

Turned from the call of the hills

To the acquisition of a careful face,

Putting a curfew on the heart.

Uncle Tan is gentle, inbred,

Completely acceptable you might say;

Traditional, a good tea drinker;

Expert on ceremonial stuff,

Never uses a premature etc.,

Correct to the last circumcising detail.

Am I stolen,

Indexed,

Into this large conformity?

__________

The first stanza discusses the situation of individuals who tried to rebel against the political system, ultimately ending in failure. These individuals had to forego "ambition" and "turn from the call of the hills". The "hills" are a symbol of freedom, representing the idea of a place free from colonial rule. Yet, individuals who refused to conform "died softly in the dispensation" and "died young". This indicates that rebellion against conformity was futile and ended in death. The juxtaposition of death in "dispensation" and happiness of "colonial days" suggests that those who tried to rebel were perhaps, silenced by rulers ("connived quietness") through prosecution. On the other hand, those who agreed to conform to escape prosecution, had to put a "curfew on the heart", perhaps implying that emotions must be sacrificed or controlled for the sake conformity.

In the second stanza, "Uncle Tan" is a common name for the everyday Singaporean 'uncle', representative of the majority of society who is considered "completely acceptable". However, the metaphor of "circumcising" emphasises the price of conformity, here: bringing to mind the harsh imagery of the removal of skin from a male's genital. Such an image strikes us as a painful experience - perhaps a warning of the price to pay for being too conformist.

Ultimately, "this large conformity" causes individuals to be "indexed" and "stolen", suggesting that conformity holds people against their will but is necessary to avoid prosecution, and for the sake of the wider society. It appears that in indexing, people have been reduced to mere numbers, and their individual stories, undermined or obliterated.

Theme like those aforementioned still runs fresh in Singapore today where people are trying to break out of societal definitions of (economic) success and constructing individual-ness in the midst of a globalised world.

In the second stanza, "Uncle Tan" is a common name for the everyday Singaporean 'uncle', representative of the majority of society who is considered "completely acceptable". However, the metaphor of "circumcising" emphasises the price of conformity, here: bringing to mind the harsh imagery of the removal of skin from a male's genital. Such an image strikes us as a painful experience - perhaps a warning of the price to pay for being too conformist.

Ultimately, "this large conformity" causes individuals to be "indexed" and "stolen", suggesting that conformity holds people against their will but is necessary to avoid prosecution, and for the sake of the wider society. It appears that in indexing, people have been reduced to mere numbers, and their individual stories, undermined or obliterated.

Theme like those aforementioned still runs fresh in Singapore today where people are trying to break out of societal definitions of (economic) success and constructing individual-ness in the midst of a globalised world.

References

(PM Lee 2004 National Day Rally Speech) Singapore Rebel blog: http://singaporerebel.blogspot.sg/2004/11/conformity-is-weakness-says-pm-lee.html

Ee, T. (1997). Gods Can Die. In Responsibility and Commitment: The Poetry of Edwin Thumboo. Singapore University Press. ISBN 9971-69-204- X

Thursday, 30 October 2014

The $ingapore Culture in Chinatown and Little India

Two places, to many Singaporeans, which hold a unique position in our society. In a multiracial nation and developing nation, these places offer a glimpse of how Singapore used to be. The reason for their initial development sprang from the "Raffles Town Plan", where the population was segregated by ethnicity. In the following years, while Singapore has tried to eliminate these divides with the Ethnic Integration Policy, places such as Little India and Chinatown have been kept as historically significant areas. At least, that is what we were brought up to understand, as citizens of Singapore.

Going there ourselves, what we saw was quite unlike the perfect impressions we once harboured. The streets and alleyways of Chinatown are now crowded with shops selling souvenirs and supposedly-Singaporean paraphernalia which mostly catered to tourists. In yet another case of ironic juxtaposition, keychain plush toys of the "minion" character (from the movie Despicable Me) hang alongside traditional amulets, trinkets, and bookmarks with Chinese names on them. We got the impression that the old had to keep up with the newer age fads in order to stay relevant, or even economically viable.

Further down the street, we see a Tin Tin Museum Shop selling merchandise at exorbitant prices (for such an area, anyway). The infiltration of Western influences in this neighbourhood is stark, and perhaps curious because surely tourists from the West would rather see something they would not be able to find at home. Nonetheless, shops like these draw the crowds - and while it seems a calculative lifestyle, it is the Singaporean lifestyle.

In Little India, we see a beautiful, vibrantly coloured, traditional shophouse-style building transformed into little more than a training organisation Avanta Global Pte Ltd, as seen below. The ironic juxtaposition of the old and the new points to the gentrification of the district, and how is has been led to co-exist in post-modern Singapore.

Many early texts written about Singapore while it was still a fledgeling nation, reflected the desire for a common culture; something which a multi-racial and multi-religious population could unite under. And thus the government, intentionally or inadvertently, provided a solution. While focusing on economic growth and domination in the region, high priority was given to education. As the Ministry of Education puts it:

Is it a safe to speculate that educational and economic success is a big part of our Singapore culture? Turning to our literature texts, we see that this is indeed one of the common themes underlying many of them.

In Goh Poh Seng's If We Dream Too Long, we can see Kwang Meng's envy, and a sort of grudging respect, for those who have both educational and economic success. While he desires to break the cycle of prospect-less employment of being a clerk, he is at the same time unable to assimilate into upper class society, because of his lack of both education and financial ability.

Similarly, in Kuo Pao Kun's The Coffin is Too Big for the Hole, we see that the officer relents at the end in part because of the financial influence the grandson holds: he has the ability to aim the eyes of the media at the funeral, something that would not be possible without significant influence. Moreover, the protagonist's monologue hints that the material value of the coffin holds more meaning to him than his grandfather's remains, highlighting just how monetary value is the dominant way of measuring worth.

In Stella Kon's Emily of Emerald Hill, Emily is revealed to be manipulative woman, even to her own relatives, to ensure that her immediate family's wealth is not lost to someone else.

Indeed, education is a as aspect of modern Singapore culture: a way in which we define ourselves, as is a means of determining financial worth. This is summed up in a ludic fashion in Hedwig Aroozoo's Rhyme in Time, where "[t]he dollar provides all your thrills. The dollar will cure all your ills". This perfectly draws out the importance we place on money, and how it lord over our daily life.

Seeing Little India and Chinatown through this new lens, we see how descriptions like "traditional" are just a part of the selling point, and hold little real meaning. They have been transformed into areas frequented by tourists and shoppers, looking for a more oriental locale for splurging compared to Orchard Road. For the sake of the buck, they have been kept in a sort of limbo: never developed too extensively to retain its traditional look, yet being fully aware that they represent a simulation of tradition. Rather than being an authentic reflection of the past, they are instead a commercialised depiction of the "good old times".

The texts may have been written some time back, but based on our little field trip, it is evident that the recurring themes of economic viability in old Singapore are still relevant in the one we know today.

Ethnic Integration Policy, Housing Development Board (HDB): http://www.hdb.gov.sg/fi10/fi10321p.nsf/w/BuyResaleFlatEthnicIntegrationPolicy_EIP?OpenDocument

Ministry of Education: http://www.moe.gov.sg/about/

Going there ourselves, what we saw was quite unlike the perfect impressions we once harboured. The streets and alleyways of Chinatown are now crowded with shops selling souvenirs and supposedly-Singaporean paraphernalia which mostly catered to tourists. In yet another case of ironic juxtaposition, keychain plush toys of the "minion" character (from the movie Despicable Me) hang alongside traditional amulets, trinkets, and bookmarks with Chinese names on them. We got the impression that the old had to keep up with the newer age fads in order to stay relevant, or even economically viable.

Further down the street, we see a Tin Tin Museum Shop selling merchandise at exorbitant prices (for such an area, anyway). The infiltration of Western influences in this neighbourhood is stark, and perhaps curious because surely tourists from the West would rather see something they would not be able to find at home. Nonetheless, shops like these draw the crowds - and while it seems a calculative lifestyle, it is the Singaporean lifestyle.

In Little India, we see a beautiful, vibrantly coloured, traditional shophouse-style building transformed into little more than a training organisation Avanta Global Pte Ltd, as seen below. The ironic juxtaposition of the old and the new points to the gentrification of the district, and how is has been led to co-exist in post-modern Singapore.

Many early texts written about Singapore while it was still a fledgeling nation, reflected the desire for a common culture; something which a multi-racial and multi-religious population could unite under. And thus the government, intentionally or inadvertently, provided a solution. While focusing on economic growth and domination in the region, high priority was given to education. As the Ministry of Education puts it:

"The wealth of a nation lies in its people - their commitment to country

... their ability

to think, achieve and excel.... teach them in school will shape Singapore in the

next generation."

Is it a safe to speculate that educational and economic success is a big part of our Singapore culture? Turning to our literature texts, we see that this is indeed one of the common themes underlying many of them.

In Goh Poh Seng's If We Dream Too Long, we can see Kwang Meng's envy, and a sort of grudging respect, for those who have both educational and economic success. While he desires to break the cycle of prospect-less employment of being a clerk, he is at the same time unable to assimilate into upper class society, because of his lack of both education and financial ability.

Similarly, in Kuo Pao Kun's The Coffin is Too Big for the Hole, we see that the officer relents at the end in part because of the financial influence the grandson holds: he has the ability to aim the eyes of the media at the funeral, something that would not be possible without significant influence. Moreover, the protagonist's monologue hints that the material value of the coffin holds more meaning to him than his grandfather's remains, highlighting just how monetary value is the dominant way of measuring worth.

In Stella Kon's Emily of Emerald Hill, Emily is revealed to be manipulative woman, even to her own relatives, to ensure that her immediate family's wealth is not lost to someone else.

Indeed, education is a as aspect of modern Singapore culture: a way in which we define ourselves, as is a means of determining financial worth. This is summed up in a ludic fashion in Hedwig Aroozoo's Rhyme in Time, where "[t]he dollar provides all your thrills. The dollar will cure all your ills". This perfectly draws out the importance we place on money, and how it lord over our daily life.

Seeing Little India and Chinatown through this new lens, we see how descriptions like "traditional" are just a part of the selling point, and hold little real meaning. They have been transformed into areas frequented by tourists and shoppers, looking for a more oriental locale for splurging compared to Orchard Road. For the sake of the buck, they have been kept in a sort of limbo: never developed too extensively to retain its traditional look, yet being fully aware that they represent a simulation of tradition. Rather than being an authentic reflection of the past, they are instead a commercialised depiction of the "good old times".

The texts may have been written some time back, but based on our little field trip, it is evident that the recurring themes of economic viability in old Singapore are still relevant in the one we know today.

References

History of Singapore, Your Singapore: http://www.yoursingapore.com/about-singapore/singapore-history.htmlEthnic Integration Policy, Housing Development Board (HDB): http://www.hdb.gov.sg/fi10/fi10321p.nsf/w/BuyResaleFlatEthnicIntegrationPolicy_EIP?OpenDocument

Ministry of Education: http://www.moe.gov.sg/about/

Poon, A.;

Holden, P.; Lim, S. (2009) Writing Singapore: An Historical Anthology of

Singapore Literature. Singapore: NUS Press.

Tuesday, 28 October 2014

Chinatown: Past and Present

Chinatown has seen drastic developments since the beginning of the city-state, though it still retains a historical and cultural significance today. Large sections of it have been declared as national heritage sites and designated for conservation by the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA).

The pictures below compare Chinatown's street scene in the 1990s and today.

|

| Chinatown street stalls in the 1900s |

|

| Chinatown street market today |

Postcards from Chinatown

Terence Heng

Racks of clothes along racks of clocks, as

if ticking away the fashion of the eras.

Fortune telling weight machine, I never

stepped on one before. Durian sign sale,

bicycle underneath no-bicycle sign.

Rusty trishaw parked outside renovated

lifts. And an old dental surgery somewhere

next to an older barber in the HDB.

Urn, three joss sticks burnt out sometime ago.

That was in the background where I walked,

background of the closed down emporium,

background of the foreign worker outside

an unopened shophouse. Background wet market,

background unanswered responses to the cajoling

from the hawkers in the background hawker centre.

Background, backstage.

Our performance dictates a different set of scripts. Souvenir shops

selling Chinese hats and fake

pigtails stapled to the end.

Umbrellas for holding water.

Postcards of nothing that we really do.

I'll sell this as distinctly local. Our whole stage of

rojak culture and the embracement of strolling

down the street back into the tour bus.

Shiny shiny trishaws and fluorescent T-shirts peddle you around

the incorporated country. This is Singapore,

ladies and gentlemen, although you don't see

the locals anywhere.

Who?

Terence Heng (b.1978) is a Singaporean, and works as a

photographer and visual sociologist. His research focuses on

diasporic, racial and spiritual space in suburban Singapore.

Terence Heng

Racks of clothes along racks of clocks, as

if ticking away the fashion of the eras.

Fortune telling weight machine, I never

stepped on one before. Durian sign sale,

bicycle underneath no-bicycle sign.

Rusty trishaw parked outside renovated

lifts. And an old dental surgery somewhere

next to an older barber in the HDB.

Urn, three joss sticks burnt out sometime ago.

That was in the background where I walked,

background of the closed down emporium,

background of the foreign worker outside

an unopened shophouse. Background wet market,

background unanswered responses to the cajoling

from the hawkers in the background hawker centre.

Background, backstage.

Our performance dictates a different set of scripts. Souvenir shops

selling Chinese hats and fake

pigtails stapled to the end.

Umbrellas for holding water.

Postcards of nothing that we really do.

I'll sell this as distinctly local. Our whole stage of

rojak culture and the embracement of strolling

down the street back into the tour bus.

Shiny shiny trishaws and fluorescent T-shirts peddle you around

the incorporated country. This is Singapore,

ladies and gentlemen, although you don't see

the locals anywhere.

Who?

Terence Heng (b.1978) is a Singaporean, and works as a

photographer and visual sociologist. His research focuses on

diasporic, racial and spiritual space in suburban Singapore.

References

(Photograph) Chinatown street stalls in the 1990s: http://www.chinatown.sg/index.php?fx=soc-archives-page&aid=5#showpage?

"Postcards from Chinatown" by Terence Heng. Last accessed 30 October 2014: https://emergencyliterature.wikispaces.com/Sec+4+-+Singaporean+Literature+(Mr+Adrian+Chan)

Terence Heng biography, Singapore Memory. Last accessed 30 October 2014: http://www.singaporememory.sg/contents/SMB-fd7433ef-4727-46f5-9e9f-a1a0d2daee8d

The Cost of Urbanisation

It is a well-known fact that compared to other countries, Singapore is but a small island nation on the world map. In fact, an Indonesian minister once derogatorily called us the ‘little red dot’ that could do little to impact the world!

Unlike other countries with fertile and arable land, Singapore is unable to mass produce agricultural goods for export, a profitable industry for countries which can. Rather, Singapore is heavily reliant on tourism as a major source of revenue.

It is only logical that more land is allocated to urban redevelopment - for the construction of entertainment hubs such as shopping malls and casinos that will attract more tourists to visit Singapore and also to spend more money. Furthermore, with the increasing size of our population, more land has to be designated for the development of living estates.

As a result, unfortunately, several buildings and monuments that may hold historical or cultural significance have been demolished to make room for urbanisation. This practice of ‘out with the old, in with new’ by the government has inspired numerous poets to create works of literature that criticise or simply depict the ramifications of urbanisation.

The two poems below highlights the problems regarding progress and urbanisation in Singapore. They portray the same matter rather differently, which is really interesting, and allow us to have insight of their personal feelings - which may possibly represent what Singaporeans generally feel.

___________________

Alas for you

Vipersonic

Alas for you

Time waits for no man

No wonder

Progress and modernism

replaces all we hold dear

Claustrophobia and fear

abounds.

Time a brutal force of nature

to itself

The phantom draws near

Rushrazor

What’s left are the remnants

of memories that once were

Alas for us

Time waits for no man

No wonder

Progress and modernism

replaces all we hold dear

Claustrophobia and fear

abounds.

Time a brutal force of nature

to itself

The phantom draws near

Rushrazor

What’s left are the remnants

of memories that once were

Alas for us

___________________

Singapore

Eileen Chong

So we beat on, boats against the current,

borne back ceaselessly into the past.

The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald

The driver, my friend, squints into the rain.

We took the wrong turn-off but Singapore

Is so small it doesn’t matter where you go.

She doesn’t know Change Alley. The new hotel

lies over Clifford Pier. I see the ghosts of red lights

at the harbour. I hear long-dead horses stamp and pull

at their tethers as wagons are loaded with sacks

swollen with rice, sugar and spices. At Tanjong Rhu

even the water’s edge has shifted. Yet a memory

of my great-grandmother’s benevolent, sepia face

swimming out from between jars at her shop remains.

I have her jade earrings now, deep green cabochons

gripped by gold teeth, mounted on stems that pass

through my flesh and hers at once. Tomorrow,

my grandmother turns eighty. For now, I wear the ring

I chose for her: a bezel-set sapphire surrounded

by diamonds. It’s not easy to find good jade

in Australia, much less old jade. The car stops

outside the botanical gardens: a fine cloud mists

the crown of trees. I watch the glossy streets and see

myself aged three, seven, twenty. It’s as though I can never leave.

___________________

In the first poem, the mood is more solemn and there is a sense of mourning over the "memories that once were" and "all that we hold dear". The negative end line "Alas for us" also almost warns of a future that can think back on few memories - which we use to define, and affirm our existence. The run-on lines in Alas for you is perhaps significant in mimicking how quickly one event of old is bulldozed and melds into the present, and how time moves seamlessly and without pause for anyone or anything.

On the other hand, in Eileen Chong's poem Singapore, the style of writing is more descriptive and the mood seems to be more personal - given that the speaker reveals details about her grandmother and memories. In Singapore, the speaker returns to Singapore after having been away, and notices all the changes the country has undergone. There seems to be a nostalgic desire in the speaker's words, but the poem ends on a relatively positive note, confident that the soul of Singapore remains amidst the changes in appearance.

The one similarity in the two poems is the fact that both the speakers seem to miss and reminisce about the Singapore of old times; and perhaps therein lies the biggest cost of urbanisation - memories.

The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald

The driver, my friend, squints into the rain.

We took the wrong turn-off but Singapore

Is so small it doesn’t matter where you go.

She doesn’t know Change Alley. The new hotel

lies over Clifford Pier. I see the ghosts of red lights

at the harbour. I hear long-dead horses stamp and pull

at their tethers as wagons are loaded with sacks

swollen with rice, sugar and spices. At Tanjong Rhu

even the water’s edge has shifted. Yet a memory

of my great-grandmother’s benevolent, sepia face

swimming out from between jars at her shop remains.

I have her jade earrings now, deep green cabochons

gripped by gold teeth, mounted on stems that pass

through my flesh and hers at once. Tomorrow,

my grandmother turns eighty. For now, I wear the ring

I chose for her: a bezel-set sapphire surrounded

by diamonds. It’s not easy to find good jade

in Australia, much less old jade. The car stops

outside the botanical gardens: a fine cloud mists

the crown of trees. I watch the glossy streets and see

myself aged three, seven, twenty. It’s as though I can never leave.

___________________

In the first poem, the mood is more solemn and there is a sense of mourning over the "memories that once were" and "all that we hold dear". The negative end line "Alas for us" also almost warns of a future that can think back on few memories - which we use to define, and affirm our existence. The run-on lines in Alas for you is perhaps significant in mimicking how quickly one event of old is bulldozed and melds into the present, and how time moves seamlessly and without pause for anyone or anything.

On the other hand, in Eileen Chong's poem Singapore, the style of writing is more descriptive and the mood seems to be more personal - given that the speaker reveals details about her grandmother and memories. In Singapore, the speaker returns to Singapore after having been away, and notices all the changes the country has undergone. There seems to be a nostalgic desire in the speaker's words, but the poem ends on a relatively positive note, confident that the soul of Singapore remains amidst the changes in appearance.

The one similarity in the two poems is the fact that both the speakers seem to miss and reminisce about the Singapore of old times; and perhaps therein lies the biggest cost of urbanisation - memories.

References

(Map) http://craftymemories.files.wordpress.com/2013/08/untitled.jpg

"Alas for You: by Vipersonic, Text in the City. Last accessed 29 October 2014: http://textinthecity.sg/poems/482

"Singapore" by Eileen Chong, Text in the City. Last accessed 29 October 2014: http://textinthecity.sg/poems/404

"Alas for You: by Vipersonic, Text in the City. Last accessed 29 October 2014: http://textinthecity.sg/poems/482

"Singapore" by Eileen Chong, Text in the City. Last accessed 29 October 2014: http://textinthecity.sg/poems/404

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)